update 28: 2007-2017

To mark a decade since work began on The Devil’s Plantation I’m writing this post as a coda to sum up my feelings about the project and how for the last four years events have conspired to keep me involved.

Made with the support of the Scottish Arts Council’s Creative Scotland Awards in 2007, the project was originally proposed as a film until the SAC informed me that as a filmmaker I couldn’t practice in my own field (unlike writers, artists etc.) Such are the vagaries of our cultural arbiters. As a compromise I suggested an interactive website with 66 short films embedded which was, inexplicably, deemed acceptable. The project was completed in November 2009. Or so I thought.

The following year TDP won a BAFTA Scotland New Talent Award in the Best Interactive Category. Two years later, my husband, having developed an app version of the website, presented me with a fait accompli when he informed the Glasgow Film Festival that I was making a feature-length film version. Completed in six weeks, the film was invited – sight unseen – to screen at the GFF to a sell-out audience in February 2013. After this single public outing it was nominated for a BAFTA Scotland/Cineworld Audience award.

In 2014, I was invited by Ferdinand Saumarez Smith of Factum Arte, Madrid, to participate in a bid to unearth the Cochno Stone, mentioned by Harry Bell in his book, Glasgow’s Secret Geometry and featured in my film. Much as I admired Ferdinand’s ambition, I wasn’t convinced of my own role in this venture or why he had solicited my interest. Clearly he hoped to find a simpatico soul or at least a filmmaker willing to document the process. After months of to-ing and fro-ing and countless group emails, permission was granted to conduct a test excavation. In September 2015, I volunteered my services by making a short film, Revealing the Cochno Stone which documents the dig.

By coincidence later that month I received an email from Ian Spring, a writer, academic and cultural commentator. Ian had been in touch with me the previous year but, for reasons unknown, disappeared after his initial contact. He was, he said, writing a book titled Real Glasgow and wished to interview me about this project. His plan for the book was to segment the city into North, South, East and West – could I suggest a walk on the southside that would fit with his agenda?

On a dreich October morning I took Ian to Queen’s Park, a place that according to Harry Bell was significant to his Network of Aligned Sites. It was also a place frequented by Mary Ross during a futile search for her neighbour, Stuart Daly. Of all the sites I visited while shooting TDP the park remains the place that haunts me most, having moved house to within a stone’s throw of its gates only days before the brutal murder of Moira Jones, an incident that resulted in a two-week closure as police searched for evidence.

Pausing at the Poetry Rose Garden, with not a rose in sight, I draw Ian’s attention to the James Hogg Memorial Litter Bin before suggesting we visit the Glasshouse and its collection of reptiles and other fauna. An hour or so later as we descended the stairs leading to Victoria Road, I talked about my latest project, Voyageuse and how I intended it as a Gesamtkunstwerk, a word unfamiliar to Ian, who asked for a translation.

In his search for Real Glasgow, Ian, like Ferdinand, plainly sought likeminded souls to accompany him on his journey but I felt inadequate to the task. Walking the city – drifting – is a solitary pursuit where only the individual can decipher the world according to their own rules and references. Ian didn’t meet me because he wished to discuss my project. Rather, I felt he was in search of answers without knowing the questions. Before parting he kindly gave me a copy of his book, Phantom Village: The Myth of the New Glasgow. It was the last I ever heard from him.

Months later Phantom Village reached the top of my reading pile. Published in 1990, Spring’s book offers an alternative view of Glasgow’s past and a doleful take on the resurgent city of the late 1980s and early 90s: the Glasgow’s Miles Better campaign, the 1988 Garden Festival and the 1990 European City of Culture. I liked the book enormously – it seemed to come from somewhere deep within its author and chimed with my own love/hate relationship with my native city. In it, I sensed a yearning for that which is gone and how the human instinct to seek out one’s past can easily trap the unwary.

Following this episode again I hoped to draw a line under The Devil’s Plantation and again the fates conspired. In July 2016, out of the blue I received a message from Colin Bell, son of Harry. Many years ago I had attempted to contact Colin in connection with his father’s book only to find the mailbox full. Colin told me how much he admired my film and asked if I’d be willing to meet. In another of a long line of coincidences it transpired he lives close to me so we arranged to meet in a Victoria Road cafe where he confessed how he had never taken much interest in his father’s work, being more into, as he put it, American culture.

Colin described his father as a prophet without honour in his own house because no one shared his love of archaeology although his sister, Sheila had proof-read Harry’s books. There was something poignant about our meeting and our subsequent – and frank – email exchange. Colin confessed that as a teenager he had a uneasy relationship with his father, describing how Harry, oblivious to social cues, displayed anger, aggrieved that his work was dismissed by ‘serious’ archaeologists whose approval he craved. Listening to Colin’s story I felt moved and, without betraying any confidences, I can only empathise with the difficulties he’s faced over the years.

Two months after my meeting with Colin and with the prospect of a full-scale excavation of the Cochno Stone in sight, again it was suggested by Ferdinand that I document the process but with no means to support the two (or more) years of work required to deliver such an ambitious project I simply couldn’t commit; I was fully immersed in Voyageuse. By all accounts the Cochno dig – and scanning of the Stone – was a success, thanks to the efforts of Ferdinand, Kenny and the many volunteers, an effort that I’m sure was appreciated by the local community. A comprehensive description of the excavation can be found on Kenny’s blog.

Mid-dig, I visited the site and watched a group of photographers and TV cameramen treading mud as they took shots of the exposed Stone. Clearly the team wasn’t short of media attention but I also realised that the moment for making a more substantial and aesthetically daring film had passed. Perhaps it wasn’t the best time to receive a call from a Los Angeles production company, Radiant Pictures.

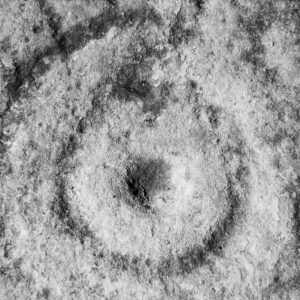

Radiant informed me they had been commissioned by the History Channel to shoot an item on the Stone – prompted by the work of Factum Arte – for a TV series on how technology solves problems. Would I be interested in working as camera assistant? Politely I declined but I did manage to source a local camera assistant for them. Shortly before its reburial, on a quiet Saturday afternoon I took a final trip to the site to view the Stone and bid my goodbyes. In stocking soles I walked across its surface, photographing the impressive cup-and-ring markings and the many recent graffiti. Here my thoughts drifted to my very first contact with the late David Marks – part-owner of this ancient artefact – who, after reading this blog, was prompted to invite me to his home with a view to excavating the Stone. What would he have made of all this, I wonder?

As I write this, the saga continues. The question of whether a replica of the Stone will be made, for whom and where, is yet to be answered. In March 2017, a meeting was held for the local community to discuss progress. Coincidentally I also received an unexpected request from Radiant to license footage I had shot in 2015. Didn’t they get enough coverage, I wonder? Rather than haggle over formats, terms, fees and deliverables I chose not to respond. My heart just wasn’t in it.

Four years on I still get the occasional invitation to screen The Devil’s Plantation, mainly from organisations that – depressingly – not only lack proper facilities but also the courtesy to offer even a modest fee for my participation. It’s the type of lazy opportunism I deplore: to create a public event with zero effort or even the slightest interest in the work itself. Films – by which I mean authored, crafted films – take months and years to produce and deserve better than to be shown in substandard circumstances. Certainly to screen TDP in such an ad hoc way would do it a disservice. Those who’ve seen the film are captured by it so I can take some gratification from that.

Perhaps at a subliminal level my reluctance to close this project speaks to a nameless disquiet, a form of grief or of letting go. In the intervening years Glasgow maintains its seemingly endless cycle of destruction/construction where month on month, year on year, the city, as Harry Bell describes in his book, is built and re-built on. In that sense Glasgow is a palimpsest like few others, where traces of the old refuse to be kicked over and where the new tends to age prematurely – the high rise towers of the schemes built in the 1960s and razed in my lifetime, the corporate blocks flanking the Broomielaw, and the new housing developments currently under construction in the Gorbals, Ibrox and the East End.

A few months ago I received a blind invitation to a book launch for Real Glasgow that coincided with work commitments in London, so I couldn’t attend. Curious to see if I’d made the cut, I ordered a copy and was unsurprised to learn that out of the many people he met on his travels, Ian Spring chose to comment on my colloquialisms, delivered – he says – in a rich Glaswegian – e.g. draw their airse (sic) along the floor, as if I was the only authentic Weegie he encountered in all his wanderings in the city. I noted too his appropriation of my use of gesamtkunstwerk that he applied to another of his subjects; that his piece on me contained inaccuracies was, I guess, par for the course.

Where Phantom Village succeeds, Real Glasgow doesn’t. For me, it meanders under the weight of disappointment, its compass cardinal points a formal imposition with little relevance to its content. I didn’t much care for Spring’s paean to the Scotia Bar, a place that always struck me as an exclusively male refuge for parochial old socialists still banging on about the Spanish Civil War in denial of the fact Franco won. What I do concur with is with his take on the Mitchell Library where he laments the lacklustre service, the loss of the Glasgow Room and the general pall of deterioration. As for his description of red and grey sandstone I disagree. In my Glasgow, there’s no such thing as grey sandstone – and nowhere else have I ever heard it referred to as such. Ever. It is, and always will be blonde – with the stress on the feminine.

One favour Spring did do was to point me towards the Southern Necropolis, a place I’ve passed a thousand times but never entered, so on a rare sunny afternoon I decided to pay a visit to Caledonia Road. A poor relation to its Northern neighbour, the cemetery was opened in 1840 to bury the dead of the Gorbals and is said to house 250,000 corpses. Passing through Charles Wilson’s A-listed gatehouse and down an avenue of cherries in full white blossom, I notice a guy in a hi-vis jacket picking up litter. I note too the newly-mown grass and the monuments, mostly 19th century, cleared of ivy. Having visited my fair share of cemeteries, the Southern Necropolis isn’t quite as derelict as some, but as a taxi driver recently informed me – I was on my way to a funeral – the current council policy is to leave headstones where they fall as a health and safety measure, citing the tragic incident of a young boy crushed to death while playing in the grounds of Craigton Cemetery, a site that features in my film and one of the most benighted I encountered in over two years of shooting.

The SN has plenty of fallen monuments, judging by the number of broken urns and obelisks rooted on the ground. In the Western section I find a recent addition, a monument to Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, Glasgow’s greatest and most neglected architect. Made of polished black Irish granite and erected by Watson Stonecraft, it bears Thomson’s name in a sans-serif font and a single five-pointed star; it is by far the most unattractive and inappropriate monument I’ve ever seen.

Thomson purchased two lairs in the cemetery in 1854 after the death of his daughter, Agnes and on his own death, aged 57, his friend, the sculptor John Mossman carved a marble bust of Thomson that was removed in the 1950s and is now kept in Kelvingrove Museum. From then until May 2006 Thomson’s grave lay unmarked. Watson Stonecraft went into administration in 2008.

In scale, material and colour and context, the Thomson Monument looks as if it’s landed from outer space. Did its designers – Graeme Andrew and Edward Taylor – refer to the architect’s work? Thomson worked mainly in blonde sandstone and employed motifs influenced by ancient orders, mainly Egyptian and Greek. He designed some of the most beautiful headstones and monuments in the city’s main Necropolis. How, with such rich references to hand, did the designers arrive at this?

In late afternoon sunlight, standing in front of the stone, I’m lost for words. It looks cobbled from a kitchen worktop supplier and worse, shows up bird shit to best effect. It bears no relationship – or in architect-speak – has no dialogue with its surroundings. Yet in a strange way, this being Glasgow, the monument is perhaps not quite so alien. In recent decades the city has made an artform of erecting tasteless piles in the wrong places: the St. Enoch’s Centre, for example, or the block of flats built on the site of the Plaza Ballroom at Eglinton Toll, cited as the ugliest building in Scotland. Or the Mackintosh School of Architecture in Renfrew Street, chosen by Richard di Marco for a BBC programme I made years ago, in which he describes the building as an excrescence.

Passing once more under the cherry blossom cloud, I leave the Southern Necropolis and walk up Caledonia Road. I pass a bus stop where a group of pensioners in their Saturday night finery chat loudly among themselves. Across the street, a man tends a garden he’s created outside his ground floor flat. A woman walks her dog. Life goes on. In that moment I’m reminded of Mary Ross’ statement, included in my film, of how one day this will all come to a stop.

The Devil’s Plantation is available to rent on Vimeo. The app of the original website is available on iTunes. Requests, comments or questions can be posted via this blog.