trip twelve: vibes

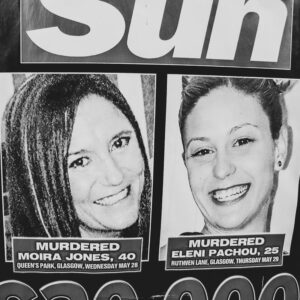

Two weeks after the murder of Moira Jones and the subsequent high-profile police investigation, Queen’s Park is reopened to the public. At first the locals, maybe hesitant, choose to circle the park perimeter while keeping a watchful eye on what’s happening behind the railings. What’s happening is TV news crews are out to solicit pedestrians in the optimism that with the right leading questions they’ll stir up soundbites about how the community – women especially – are now too terrorised to enter the park alone, day or night.

On the morning of the opening, I walk with a friend and her dog. Passing through the entrance gates at Queen’s Drive and Victoria Road, we note how the police still maintain a strong presence. We head in the direction of the abandoned bandstand where – according to reports – the partially-clothed and battered body of Moira Jones was discovered. Arriving at the spot, we’re confronted with piles of dense, withered shrubbery, hacked down by the police in their search for clues.

Even on this bright sunny June morning, there’s a palpable air of dread as we stand in front of a shaded pathway. My friend’s dog, normally a boisterous creature, senses something amiss and refuses to move any closer. In truth, nothing’s changed here but given our lack of knowledge of what actually occurred and with our Glaswegian capacity for tale-telling, we speculate like crazy.

I return to the park the following Monday for some unfinished business – to shoot the discernible signs of the Camphill Earthwork. This involves straying from the paths and setting up my camera in the more remote and sheltered areas on higher ground, away from the usual joggers, dogwalkers and cyclists. One thing I do notice – to my disappointment – is the rubbing-out of the UNT graffiti on the stairs and flagpole rampart. I’m looking for clues – traces of mounds, scarps and depressions that suggest some kind of structure. In an article published by Horace Fairhurst and Jack Scott, (1950-51) I read a dry but informative description of an irregular oval, roughly half a mile long, rising at the WNW end to an altitude of 200 feet and formed out of boulder clay. The stones are easy to find, but the spread and shape of the oval are elusive to the untutored eye.

While shooting the boulders in the central area of the Earthwork, I’m surrounded by dense bushes and undergrowth and every sound becomes amplified in spite of the roar of circling helicopters overhead. On the ground grey squirrels dart through long grass, chasing and tumbling. A magpie suddenly bursts out of a tree. But when I hear footsteps trudging through the grass, growing closer, my heart almost stops. A fleeting thought occurs – surely there must be hundreds of dead bodies here – the troops defeated at the Battle of Langside, for one. Or how about the earlier inhabitants, would they not have been buried here? While archaeologists write reams about shards of pottery and millstones, what of the dead? Have they turned up any ancient bones lately?

Out of a copse come two cops, one male, one female. The pair are surprised if bemused to find me standing with my camera and tripod. I supply the answers to their questions and while we talk, out from the undergrowth appears a man – he’s maybe late 20s, with cropped blond hair and casually dressed. He looks to be scattering something on the ground, as if feeding birds. At first he’s oblivious to our stares but when he does he acts unconcerned. The police officers venture the theory that Hill 60 and its environs provide a venue for gay cruising, alongside Cathkin Braes and Kelvingrove Park.

Next the police officers ask if anyone knows I’m here. No, I tell them truthfully. Have you got a mobile on you? No, I reply, suddenly feeling stupid, it’s at home charging. Anyway, I offer, you’d think Queen’s Park is the safest place in Glasgow right now. They give me a reproachful look. I take the hint and as I pack up to leave they head off in pursuit of the man, who by this time has vanished back into the undergrowth.

Standing at the flagpole I recall Harry Bell’s account in a later edition of Glasgow’s Secret Geometry of how Marsha, an American psychic, visited the Earthwork –

I dwell on this while looking through the viewfinder towards the Gorbals where only a couple of weeks ago, the Stirlingfauld flats stood. If there were three circles, I wonder, just how far might they have spread? Further than the confines of the park? Across the entire city perhaps? The notion of three is compelling, if not downright seductive, and particularly three rings, having such provenance in occult symbolism. I’m going to have to follow this thought, I promise myself.

Suddenly I’m interrupted by another two police officers, this time two men, one young, the other more senior. They enquire again as to what I’m doing and again I explain, although I omit to mention Marsha and her three-ring theory. By now I’m aware of how ridiculous my story’s beginning to sound, but all the same, I’m grateful to Strathclyde’s finest for keeping an eye on me while I’m chasing my tail at the scene of such a raw and recent crime.

Hi May,

Good to see you again the other day in GFT after so many years!

The Devils plantation blog is very interesting. I look forward to reading more and seeing the finished work.

Hope to see you again soon.

Jack

Thanks Jack,

Still got a long way to go! But I’m shooting some interesting stuff – funny the way the city’s constantly shape-shifting. It’s hard to keep up!

best wishes,

May