update 23: cochno news

When I embarked on TDP back in 2007 often I got lost while out on field trips despite having a map. Anyone following my journey knows that the most elusive of my destinations was the site of Cochno/Druid Stone. Of all the places mentioned by Harry Bell in his Network of Aligned Sites, at a psychic level it seemed as if the Stone was taunting me. Eight years later and it’s still a lost cause.

Bear with me. This is a long and convoluted plot with a large cast of characters.

Last summer, a journalist called Craig Brown wrote a piece in The Scotsman about the Cochno/Druid Stone. He was prompted in part by the film version of The Devil’s Plantation which around that time screened three – yes, the magic number recurs – times in as many months. Previously I had explained to Craig my limited knowledge of and exposure to the Stone. So I was delighted when he told me that he had been in contact with Mrs. Elaine Marks – currently owner of one-half of the Stone – and how she hoped to meet me again, two years after our first encounter.

Prior to the publication of Craig Brown’s piece there had been a low, mainly local level of interest in the Stone. Many months before I was invited through a Facebook group named Indigenous Archaeology in and around Milngavie (IAM) to join another group called ‘The Campaign to Uncover the Cochno Stone’ to which I contributed a few likes, shares and comments.

Soon I learned that with no consultation I was made an administrator of said group. When Craig Brown’s piece was published, attracting around 10,000 likes, there was a spike of Facebook requests for access to the Cochno Stone group. There was also talk among the members about a potential film about the Stone. Fine, I thought, but include me out because, practical production issues apart, I couldn’t see a story – besides, the odds of an excavation actually occurring were too short and with no funding or strategy for the Stone itself and given Mrs. Marks’ concerns about her garden I felt the project was a non-starter.

The Scotsman article was followed by a jovial riposte in The Herald and a short item on BBC Radio Scotland. Clearly there was interest in the Stone but with other work commitments I had no time nor the desire to lobby for its excavation and so quietly withdrew from the Facebook group.

In September I sent a card to Mrs. Marks with a copy of Craig’s article and soon after we met for lunch and spent a pleasant few hours talking not about the Stone but of family matters, interior design and a new film based on the life of my late mother-in-law, Erica Eisner/Thomas.

Fast forward to late October 2014 when I received an intriguing email from Ferdinand Saumarez Smith at a company called Factum Arte based in Madrid. Ferdinand described how he had been in contact with Glasgow University Archaeology Department and Historic Scotland with a proposal to conduct a temporary excavation of the Stone for the purposes of replication – he explained how Factum Arte and the Factum Foundation are world-class in 3D scanning, art fabrication and conservation. Would I like to be involved in some way?

Cochno. Maybe?

After giving it some thought, a day later I replied to say I thought his idea, to replicate the Stone with a view to an exhibition was the most exciting and viable proposal I’d heard of, albeit subject to the planets aligning due to the number of parties involved and practical considerations of unearthing and scanning a 55 foot artefact on site. But, I told myself, what if?

Over the next few weeks I swapped many emails with Ferdinand. Inevitably, the subject of making a film documenting the process was raised. In late November he invited me to visit Factum Arte in Madrid, a chance I wasn’t about to pass on so with my curiosity piqued and with my husband in tow in early December we flew to Spain.

In an unassuming corner of the city we arrived at a set of light industrial sheds where we were introduced to the staff, including Adam Lowe, Factum Arte’s founder and Richard Salmon, a conservator of ancient artefacts and consultant to many of the world’s leading museums who had flown in from the south of France to talk specifically about the Cochno Stone. Ferdinand kindly gave us a tour of the premises, less a set of workshops than a series of magic caves where we saw the most incredible replications of ancient artefacts, fantastical new works created from the drawings of Piranesi and bespoke works commissioned by leading contemporary artists.

To say I was impressed is an understatement – having worked in set design in a past career I’m familiar with what goes on in contractor’s workshops so I’ve always appreciated what’s still known in film and TV as ‘craft effort’. I’m certain if Renaissance artists had access to 3-D printing and scanning technology they would have exploited it.

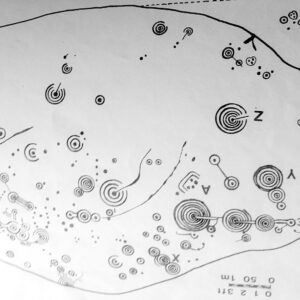

The following day we met Ferdinand and Richard at the airport to return to Scotland. A site visit had been arranged with John Raven of Historic Scotland, Kenny Brophy of Glasgow University Archaeology Department and Donald Petrie of West Dunbartonshire Council to determine the viability of the project. We duly arrived at Cochno Road on the eve of a huge storm, the so-called ‘weatherbomb’ of last winter. In sheeting rain and sleet we gathered at the site of the Stone which during the summer months is hidden by tall bracken. Now with the land bare, I got a glimpse of its scale – and was slightly alarmed by the few trees firmly rooted on it, causing speculation of permanent damage.

While debating the logistics, several thoughts crossed my mind. Foremost – could Mrs. Marks be persuaded to grant permission? Having alerted her to this new proposal I knew she was reluctant – understandably – to allow access to her three-acre garden. How might she be assured? It was a thought shared by Donald Petrie and at time of writing, a matter still to be resolved. A second thought came as I scanned the horizon in the direction of Faifley, the housing scheme close to the site whose occupants were supposedly the reason for the Stone’s burial in 1964. How could the site be made secure during the process?

My last thought I didn’t relish because it meant facing up to the perennial problem of a film. I confess my heart sank a little as I contemplated what it would take to produce and direct a film of sufficient weight and depth that would do more than just merely document the process. Or avoid becoming yet another factual TV doco with all the requisite elements, namely presenter-led with the standard measures of ‘jeopardy’ and ‘human interest’ typically demanded by broadcasters. Moreover, I wondered, how best to fund a film about an obscure 5000-year-old stone buried in a remote corner of Glasgow?

I know what it takes to develop, finance and produce a film. That is, of course, suspending my view of film as an elevated hobby or passion like building matchstick palaces say, or circumnavigating the globe, the former being relatively cheap while the latter is ruinously expensive. These days thanks to cheap kit and software, film can be both. In the cheap scenario, however, what costs is time – the amount needed for physical production with no crew or any of the support enjoyed by high budget productions. It also requires experience, another form of time invested, often over decades, to acquire the skills and sensibility of how to tell a good story.

While musing on this, I reflect on the time spent producing The Devil’s Plantation where in the course of its making I earned far less than minimum wage. But even the lowest budget film needs hard cash: apart from camera and sound kit and computers and software, there’s expendables such as data cards, plus the cost of travel and food and even the electricity bill to consider. And that’s before you get paid even the most meagre wage.

It’s every filmmaker’s challenge. So how do you get paid for your graft? Access to public funding is limited by T&Cs and is generally oversubscribed. The same applies to broadcast. Looking at the guidelines for STV/SDI’s recent initiative This is Scotland I note that the budget, pegged at £30K for a broadcast half hour, suggests little or no crew, or at least a crew on the current agreed rates of pay. There’s always crowdfunding of course but as anyone who has gone down this route will testify, to fund a film by this method is a full-time job between shooting promo pilots, writing pitches, offering incentives and by making yourself permanently visible on social media with no guarantee of ever reaching your target.

Recently I had the dispiriting experience of going through the public funding grinder with my latest project, Voyageuse. After many weeks of negotiating with a partner organisation (the CCA, Glasgow) to back my project and meeting/calling/emailing Creative Scotland, I spent four weeks form-filling followed by a three month wait only to receive a two-line rejection email. I mention this only because I’m aware I’m not alone in this experience of ‘engaging’ with ‘enablers’. Of course, not every project will secure funding – nor should they – but my regret is the time – a precious commodity – wasted on such an unedifying exercise.

More positively, I’ve decide to make the film anyway by exploiting what I already own and by self-funding. It’s an ambitious undertaking and one that will keep me busy over the coming months. If you’re inclined, you can follow the project on my new blog and on Twitter.

Where this leaves the ongoing Cochno Stone project, only time will tell. Naturally I would love to be part of it because if nothing else I’d like the story of the Cochno Stone to have a happy ending and also as a tribute to Ludovic McLellan Mann, David Marks and all of those with a spirit of adventure. As I write, Ferdinand is about to go down the same funding route I chose, so I wish him well. At least the Stone’s not going anywhere anytime soon.

Good luck with it May, it’s a good story.

If I can be of any help with my limited final cut editing skills for some donkey work it would be a good learning experience for me although I’m sure you’ve got it covered! xxx

Thanks Jaine – I’ll bear that in mind because I’m plenty busy on my new project! I swapped my own FCP for Premiere Pro CC after Apple introduced Final Cut X. With any luck I might get to make a film about the Stone yet! I can’t seem to shake it off.

All the best,

May