trip nine: viewpoint

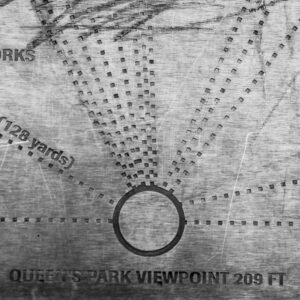

It’s the late May Bank Holiday Monday and for once I’m blessed with light. Grabbing my chance and my camera kit I return to Queen’s Park in the evening to shoot video of the Scottish Poetry Rose Garden and the viewpoint from the hilltop close to the flagpole where a sign points out the landmarks radiating across the city.

Parked illegally at Goals, I unload the kit, passing the 5-a-siders. From here it’s a short walk to the Rose Garden. The late sun throws its beam over trim lawns, burnishing the ancient conifers and lending the scene a fairytale surreality. A small set of steps leads to an unmarked stone, squat, roughly square and obviously of some significance but of what I have no idea. At first I assume it’s a naked plinth, some monument gone awol, but closer inspection shows no sign of a statue having been mounted. Another unsolved mystery. After my encounter with the man on Hill 60 on the previous Friday, I’m in sleuth mode. Through my viewfinder everything looks suspect. Even the James Hogg bin looks planted.

In truth, there’s not much to see. Shouts reverberate from the football pitches and the air is high with rose and honeysuckle. Now that virtually everyone owns the means of film production, my camera goes unremarked by the few passers-by. Besides, in this city it’s assumed that anyone out shooting with more spec than a mobile phone is working on the TV series, Taggart, whose lead actor, the late Mark McManus, was a regular at the nearby Queen’s Park Café on Victoria Road, the pub, not the ice cream parlour.

At the Queen’s Drive entrance I plant my tripod to shoot the wide tree-lined avenue and the staircase leading to the park’s summit. Now the light lies low, casting long shadows across the path. Unable to commit to shooting in colour or black and white, I take my time to meticulously duplicate each shot. At this stage of the project, I’m still debating with myself about how these moving/not moving images will eventually look. The photographer, Walker Evans, favoured monochrome and believed colour was ‘too emotional’. The filmmaker, Andrei Tarkovsky, also referred to the emotion of colour and tended to desaturate the colour in his work. Personally I’ve always maintained that Glasgow is made for black and white photography and judging by the work of the city’s documentarists – from Thomas Annan to Oscar Marzaroli, Joseph McKenzie and Harry Benson, I’m not alone, though to me the city’s palette is less about shades of grey than dark and light.

As I muse on this, in the distance, two cyclists tear downhill towards me, male and female, somewhere in their mid-20s. Bemused, they pass the camera then screech to a halt, breathless, waiting for the explanation. A long story, I tell them, noting how their cycles are brand new and identical. The guy sees me eyeing the bikes. Forty quid each out of Tesco’s, he informs me, total bargain. I hope we never spoiled your shot, offers the girl, if you want we can do another take, adding, will it get shown anywhere? Take? Everybody’s in on the jargon, I think but don’t say. I hope so, I reply, and thanks for the offer. Well, if we end up in your movie, don’t forget – the name’s Brian Mackenzie, says the guy. And I’m Gemma, chirps the girl, Gemma McManus. McManus? No relation surely to Mr Taggart? No, I won’t forget, promise, I tell them and they speed off ‘for munchies’, says Brian, winking at me as they go.

I’m left looking for signs, anything to help me make sense of this place. Camphill Earthworks is a significant place in Harry Bell’s Glasgow Network of Aligned Sites, a main spur linking several other sites. Tired now, I haul the kit up the main avenue, passing a young woman in full black sack, walking alone, almost spectral. Pausing at the foot of the steps, I note the curious wrought iron railing, a set of double unclosed circles each with an upward-pointing arrow, subliminally phallic. I take my shot and mount the stairs, buckling under the weight of my thoughts and my load. Then, on the ground I see a sprayed message – UNT – closely followed by a second UNT. If the graffito’s designed to urge the viewer into filling the blanks then it’s as bold and provocative a piece of art as any I’ve seen lately.

From here it’s all uphill. The daylight’s beginning to fade now and I worry I’m too late to capture the view. To my right a gang of tweenies squeal: apprentice flirts, amateur shaggers, they’re doing their time, teasing and chasing their way downhill. I keep a tight hold of my camera as I climb the hill. Then all is revealed, but it’s not what I expected. Sprayed on the wall under the flagpole is the legend – UNTOUCHABLES – the problem of the UNT beautifully resolved. Catching my breath I turn to the view. Although the treetop foliage mars the panorama, I experience what screenwriters call the moment of recognition. Well, in a tiny way. The city is laid out, undulating to the hills north and west, Dumgoyne looming dark and large in the west. Little wonder that Camphill was such a prime site in ancient times.

Standing on this hill I’m reminded of Harry Bell’s revelation while travelling on the top deck of a bus heading north up Victoria Road. For a fleeting moment he glimpsed the roof of Glasgow Cathedral and suddenly realised a possible link from the south of the city to the north. It’s admirable that Harry, no doubt with worldly concerns on his mind, could simultaneously be driven by his passion for the unknown – the notion of a connection between the Camphill Earthworks and the Necropolis, another highly significant site in his network. And because he found it, because he dared to believe in it, it appears obvious to anyone who can be bothered to look.

Hi,

Your “naked plinth” is/was the base for a sundial. There was a brass repro made in the early ’90’s……Then stolen.

That wee raised bit is the remnants of a greenhouse

Thanks Adam,

I thought it might have been a sundial or some kind of sculpture.

Cheers,

May