Across the world, things are happening that no prayers or pieties can undo, events so terrible they make the dysfunctional nation I call home appear normal. Here on the periphery of Europe, I have the luxury of thinking about writing and filmmaking. On a good day it’s my highest aspiration. On a bad day, it’s a lost cause. I'm not alone. Many in Scotland share the same thought - how can I have a career in the arts or creative industries and not die of disappointment?

For the working classes today there’s no route to becoming a professional anything in the arts, not when the portal to free higher education was slammed in our faces last century. Whether through creativity or patronage, art is once again restored as the plaything of the moneyed, the unpaid interns able to work for free at the expense of those who can't. In this context and in the absence of a living wage, who gets to make art?

In my own field, a film is what one makes in one’s spare time; a hobby, a craft even, but it’s not art. It never is art. In this country we don’t make films-as-art. Artist films can and do exist but opaque commissioning practices make its arbiters paragons of exclusion. Elsewhere we make content underwritten by public funders and broadcasters that might, if one is lucky, screen at the occasional film festival or be transmitted to audiences too small to count by any streamer that will have them.

At the EIFF-sponsored Industry event, Distribution Rewired in 2018, the CEO of MUBI remarked how a feature-length work might earn $800-1000 for a short-term deal, typically non-exclusive for a month. No filmmaker can pay themselves minimum wage let alone fill their boots on this model.

To quote Lenin, channelling the novelist and nihilist, Nikolay Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky, What is to be done? In the context of Scottish culture, the age-old question is unanswered, mired in the complacency of we, the colonised and led by those with a lack of political will or strategic competence.

Money helps, though I don't believe funding - or its lack - is the problem. Rather, it’s how public money has, for generations, been squandered on the wrong line items, chief among which is an excess of administrative, not creative roles, jobs occupied by the middle classes who corral the low-waged new and emerging through fiery hoops of sit-up-and-beg initiatives. It speaks to why public funders don't solicit applications from the old and experienced unless, of course, they've been anointed elsewhere and whom, by that stage, get their funding elsewhere. The rest of us are personae non gratae. The idea, that mid-career filmmakers (and I exclude TV directors) even exist is so much fairy dust in a fart.

Dwelling on the fate of those might-have-made-its, I’m struck by the commentary surrounding the release of Yorgos Lanthimos’ film adaptation of Alasdair Gray’s novel, Poor Things (2023). There’s two sides to this: the first, from those convinced that, by eschewing Glasgow and relocating the plot - and production - to London, Gray and his native city were somehow betrayed and that the film should have used Scottish-based talent. Which in the real world would never have happened since the film credits ten producers of various stripes. Try finding ten Scottish film producers. I promise you can't.

Those who say Poor Things should have been homegrown betray a wilful ignorance of how film works and how few companies, financiers and distributors take a punt on Scottish talent. Those who succeed - mainly directors - tend to leave because there’s no regular remunerative work to be had. The reasons are eternal, complex and - as my regular readers know - hardly bear repetition because simply it's the truth. I could fill volumes with the slights and slanders, insults and injuries that I - and many of my peers - have experienced in our efforts to contribute to the national film culture, but it's too exhausting.

The irony of the deeper cultural significance of Poor Things isn't lost on me. Gray's intention for the novel - a metaphor whose protogonist, Bella Baxter - aka Bella Caledonia - mirrors the nation's quasi-schizophrenic schisms and duality - a country sundered by external forces told through the presence of a woman similarly exploited through language and the erasure of her past. Was it the filmmakers' job to propagandise this underlying thesis for Scotland? No, definitely not.

A second view, one I share, demands a grasp of international co-production, talent packaging and sales required to make a film of ambition and scale, the kind of film that no doubt Lanthimos described to Gray, prior to the author’s death in December 2019. Namely - you make the best film you can by any means avaiIable. I was saddened - and angry - to learn that Gray, alongside his late contemporaries, the poet, Tom Leonard and the recently deceased artist/writer, John Byrne, was overlooked by BBC Radio 4’s obituary show, Last Word - an indictment of what London thinks of Scotland's cultural greats.

Can Scotland really be so benighted? In early January, while boarding a flight to Spain in wind and horizontal rain, I remarked to my husband, apropos nothing, how I was 'done with this place.’ It was the first time in decades I’ve expressed the desire to leave. Perhaps the thought is linked to my recently-acquired Irish citizenship (my husband is now Austrian as a result of our research for Voyageuse) or it came from some deeper well of despair. That, and the start of another year, who knows?

Over a century, the list of Scottish directors/writers/actors forced to leave makes me weep. In fact, what passes for my own career could be construed as a failure. Not because I lack the requisite skills and talent, but because I had no option but to leave: to London in 1984, to Berlin in 1997 and on short stops to the US, Hungary, Spain, Denmark, Russia among others in pursuit of my work. My true failure was to return under the delusion that Scotland, like Ireland, could one day become a prolific filmmaking nation.

Since I wrote this piece for Bella Caledonia in 2017 about the lack of joined-up thinking on the matter of a Scottish Film Studio, I'm pleased to report how in the intervening years some decent four-wallers have been built, but these are occupied largely by high-end TV productions, whose Heads of Departments and senior production staff come from within the M25 circle. I don't doubt jobs have been created by the new studio spaces but how many of those are above-the-line?

I recall a meeting years ago with the then-CEO of Scottish Screen, Ken Hay, later CEO of the Centre for the Moving Image, who stressed how ‘television, not film, is the driver’ of the next 20 years of screen activity in Scotland. In a way, he wasn’t wrong since funding for film in Scotland was limited to shorts schemes that might have given breaks to wannabe filmmakers, but very few of whom parlayed it into features or careers. The cinematic, whether shot on film or acquired digitally, was abandoned in favour of TV drama, a form driven by the literary rather than the visual, too often made on low budgets and suicidal schedules.

While Hay was correct, his prediction succeeded only because of a lack of political will and by boosting TV at the expense of film production and championing the ‘get me coverage’ ethos of TV in the 1990s and 2000s. Streaming was 20 years on the distant horizon but rather than nurture a new generation of filmmakers, in his role as CEO of Scottish Screen and later at the CMI, Hay presided over a debt of over £2 million and was instrumental in the demise of the Filmhouse, Edinburgh, the Belmont Cinema in Aberdeen and the Edinburgh International Film Festival.

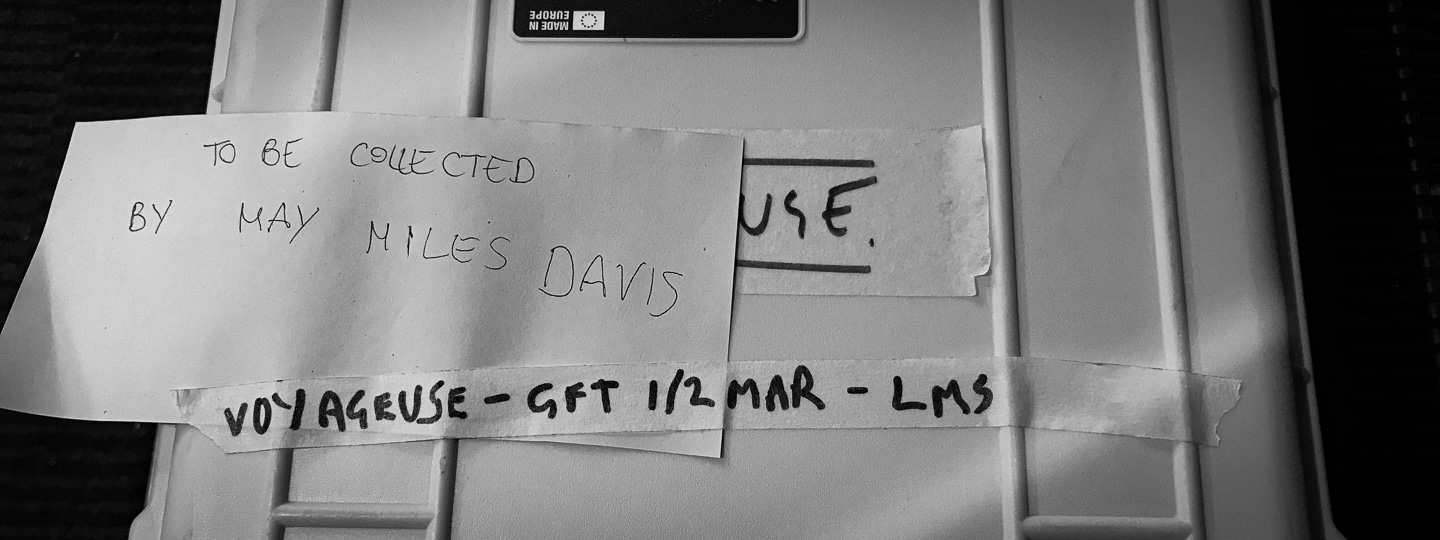

Meanwhile in my native city, the Glasgow Film Festival recently launched its 2024 programme. Last November, sadly, I was rejected as a potential mentor for the GFF Industry Mentorship Scheme. This, of course, is their prerogative, although when I sent my initial email I sensed I would never hear back. And I didn’t. My question - why wasn't I given the courtesy of a rejection? - was met with indifference masquerading as a reasoned explanation. This is a shame but unsurprising when the GFF, where my work has screened on two occasions, managed to misname me when I collected the DCP of my last film. I figure if I were in my 20s, say, it may well have been a traumatic and triggering experience.

Of necessity there are reputations to protect when public funding is involved and good grace ought to prevail. Following an email exchange with the GFF Artistic Director and GFT CEO, I recalled the last time we interacted when, in October 2018, I was invited by her to the Light House Cinema, Dublin along with a talented young filmmaker, Douglas King to screen our latest films in a cultural exchange facilitated by the Scottish Government Office in Ireland.

At the time I was genuinely pleased to screen Voyageuse and, judging by the audience response at the Q&A, and the spontaneous applause I received when I remarked how the film was ‘really about love,’ I made sure to mention all the sponsors in my intro and to speak to the ‘right’ people afterwards. Only later it struck me how the only two indigenous films Scotland had to show for itself that year were made on absurdly low budgets as passion projects. Was this all my country could offer? Two micro-budget films, unsupported by our national funder, Screen Scotland, yet there we were, shepherded to deliver a message: that all was well with Scottish film.

It’s ironic that 25 years ago, following the critical success of my debut film, the Irish Film Board invited me and my partner to advise on how to make micro-budget films in a way that accommodated union rates and other contractual issues. Our model was later adopted by Film London’s Microwave scheme. What they learned from Elemental then, and everything I've learned since, I believe, may well help an emerging filmmaker today. After my knockback from the GFF, I've considered launching my own mentorship scheme but after many discussions and for numerous reasons, I'm still undecided.

Of course, Poor Things could never have been made by a Scot in Scotland with a Scottish cast and crew. Until the reasons why not remain unspoken and unresolved, nothing will improve. How many great contemporary Scottish novels been robbed of a chance to appear on screen?

For instance, where was Psychoraag?

Or The Voids?

Or Close Your Eyes?

Or The Panopticon?

Or Brodie?

Or The Cutting Room? - which almost became a film in 2004, adapted by Andrea Gibb and with Robert Carlyle attached as the lead, but was eventually binned.

I could do this all day, every day – listing titles written in the last twenty years or so that I admire but which in all likelihood will never become films. I remind myself that Scotland, with its fourth-world film ecology is tethered to England where, when it's not making heritage movies, unsuccessfully apes Hollywood. Indeed, wherefore the English BAFTAs?

Personally, I’ve long wanted to direct a contemporary take on The Sins and Confessions of a Justified Sinner by James Hogg that, according to Andre Gide writing in the preface of my 1947 version, is the first truly psychedelic novel. In a similar vein, in 2001, a Scottish producer asked if I would be interested in adapting Irvine Welsh’s Maribou Stork Nightmares. Later, I was asked by another local producer to adapt Janice Galloway’s autobiography, All Made Up before she tried to make it for TV and failed. There are others, many others and it breaks my heart to think of them. They are our unborn.

Original storytelling isn't the problem. Scotland has writing talent galore across all genres and styles that reflects its culture, its people and how they see themselves. It's the very least a mature country should offer. This isn't a call to indigenous filmmakers to limit themselves to adapting native novels, worthy as so many are, but what does this lack of cultural output tell us about ourselves? I'd ask the director of Screen Scotland, but he chose - childishly - to unfollow me on social media. The Glasgow Film Theatre and Glasgow Film Festival have never followed me, the only native Glaswegian writer/director of repute excluded by them.

The above image is of my DCP for Voyageuse labelled to be picked up by 'May Miles Davis' from the Glasgow Film Theatre. After I picked it up, I realised this wasn't a jovial nudge from someone on the staff who knows me. It hurt me and was really, totally ignorant.

I am SO done with this place.